May 2021

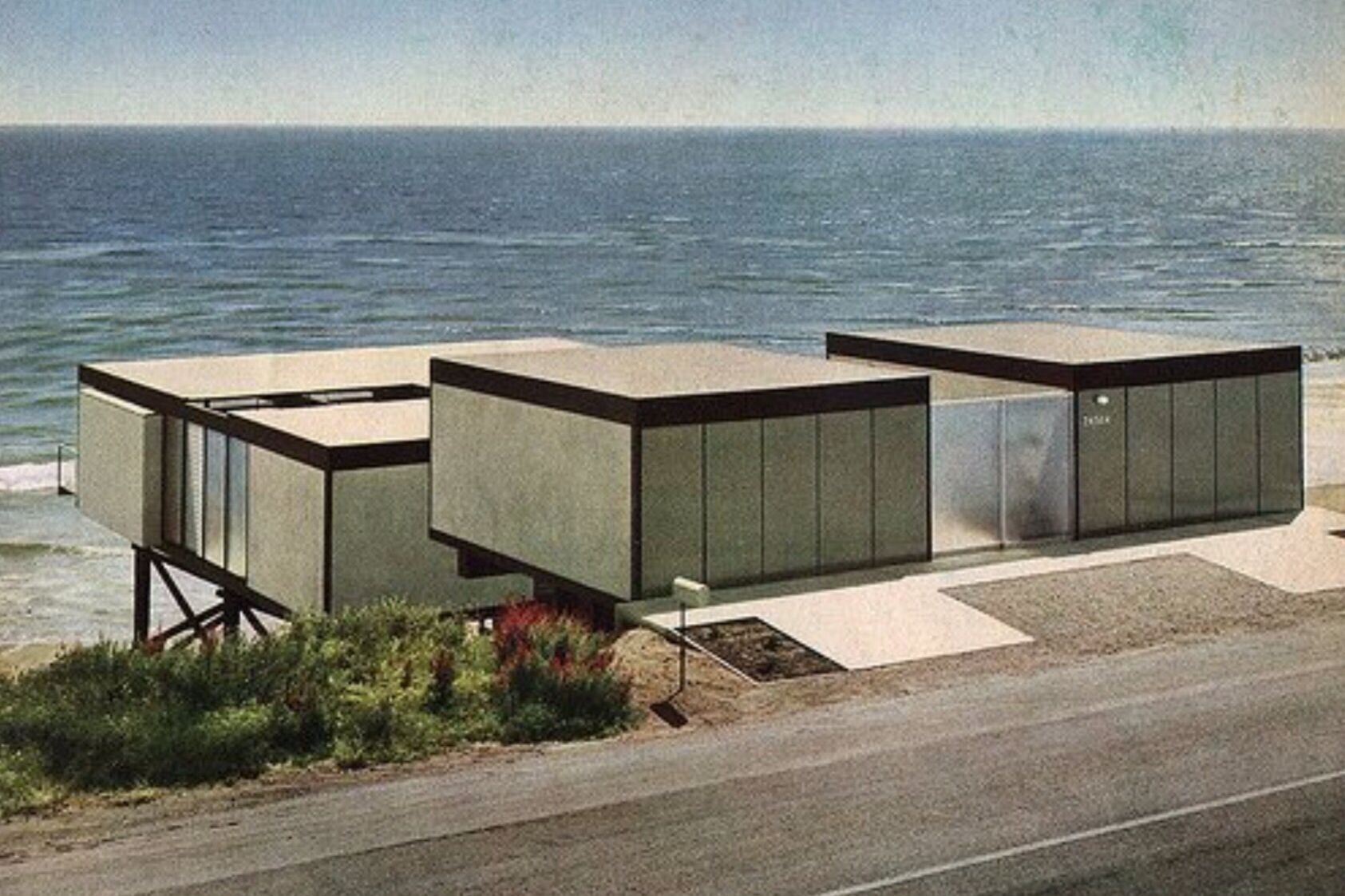

Hunt House, Craig Ellwood, Malibu, 1955

Los Angeles is a city that keeps luring architects back. A rich confluence of factors converged following the Second World War to create an unparalleled mid-century architectural pedigree. A cluster of young enthusiastic architects embraced the momentum of the design revolution in Southern California during this period, including Craig Ellwood, a designer who across his career mastered the ideals of the generation. Ellwood was able to perfect the blending of functionalist International Style doctrine with the informal exterior focus of the new US western frontier.

Ellwood’s name is often unheralded, with the mid-century era instead focusing on the likes of Eames or Neutra. Although, it was Ellwood’s projects, photographed by Julius Shulman and featured in John Entenza’s Arts + Architecture publication that helped to cultivate the energy of the period in Southern California. Ellwood’s work is increasingly revered for its artful ability to soften and humanise the heroic scale of modernism, creating inviting and fulfilling spaces from simple and efficient building systems. Over nearly 30 years Ellwood nurtured a firm that prioritised structural rationality and superb taste to create an elegant body of work that unlocked eternal truths about simplicity in design that continue to influence the work of architects today.

Entenza House (Case Study House #9), Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, Los Angeles, 1949, Photo: Julius Schulman

Craig Ellwood was born Johnnie Burke in modest small town Texas. After seeing a sign for Ellwood Liqors, and thinking that Craig sounded like an American hero’s name he changed his name to Craig Ellwood and made the big shift to the bright lights of Hollywood. Upon arriving in Southern California he initially wanted to be an actor and worked as a model before ending up in a cost estimating course at UCLA.

Following the course he soon found employment as a cost estimator in the evolving construction industry in Los Angeles. This role encompassed working on some of the seminal early works of the era, including the Eames House and the Entenza House. These projects exposed Ellwood to the importance of the organising principles of buildings and an astute eye for efficient design. He promptly developed an expertise for understanding materials and construction that continued throughout his career. This knowledge clearly impacted his design ideology throughout his career, with clear, simple and efficient structural layouts integral to both his aesthetic and cost strategies of his projects.

Eames House (Case Study House #8), Charles and Ray Eames, Los Angeles, 1949-50, Photo: Julius Schulman

Inspired by his work on these projects, Ellwood eventually transitioned from a cost estimator to a residential designer himself. Whilst he lacked formal qualifications throughout his career, he was able to create architectural solutions that seemed free of the burden that the full rigour of the architectural curriculum can often create. Ellwood practised and marketed his skills like he had something to prove, potentially in part due to the questions around his qualifications. This constant motivator pushed Ellwood to achieve architectural outcomes that surpass the skills of nearly all fully qualified architects of his time.

Ellwood’s decision to pursue a career in architecture aligned with the booming post World War II housing growth and a keen desire for change of ideas from all those reopening after the war. Into this space arrived a series of people in Southern California who were able to grasp the growing public acceptance of modernism. The path had been set by the interwar generation of European Bauhaus educators and it was now ready to be domesticated on the larger scale across America. Ellwood’s life may have started humbly in Texas, but it would be he that would eventually maximise the functionalist ideas of Walter Gropius through feminizing the engineered box into a fine-tuned machine for living. Ellwood’s houses to this day stand as the personification of the Californian dream.

Ellwood is the first to admit that his earliest works were too derivative of either Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier. He was soon able to start to develop his own unique style of structural efficiency, instigated by the need to be frugal with project budgets. This mindset suited the growing trends set by the European émigrés architects in the US that were preaching the progressive ideas of functionalism and material efficiencies in construction. Ellwood used this to develop a mantra of lightweight structures, meticulously refined, which suited and enhanced the informal lifestyle that Los Angeles prompted.

Anderson House, Craig Ellwood, Pacific Palisades, 1954

The Anderson House in the Pacific Palisades, was a formative early project that started to realise Ellwood’s unique design ideas. This project was one of the first instances of Ellwood exploring the simplified box for living. This particular project finds true joy in the natural material palette, effortlessly blurring the tactile interiors with the bush setting of the heavily vegetated site. The result is a timeless solution driven by a pursuit of refinement. Always governing these functional decisions was Ellwood’s impeccable taste, which pushed these cost effective projects along a rarely achieved path of being beautiful projects without the need for cost prohibitive budgets.

Anderson House, Craig Ellwood, Pacific Palisades, 1954

As Ellwood’s confidence grew his design outcomes began to inventively explore further the language of Constructivist and European Functionalist styles of architecture. The Hunt House in Malibu is a fine example of how Ellwood was embracing these theories in pursuit of low-cost rational solutions that use industrial methods and materials to prioritise the act of living. The Hunt House is able to realise the Bauhaus endeavour of combining art and industry through a modest form, constructed of everyday industrial materials, to achieve a built outcome that exudes true levity and joy for the act of living. This demonstrates how modern building methods when executed with the highest levels of taste, can achieve cost effective, beautiful houses that maximise the aspects of indoor/outdoor living.

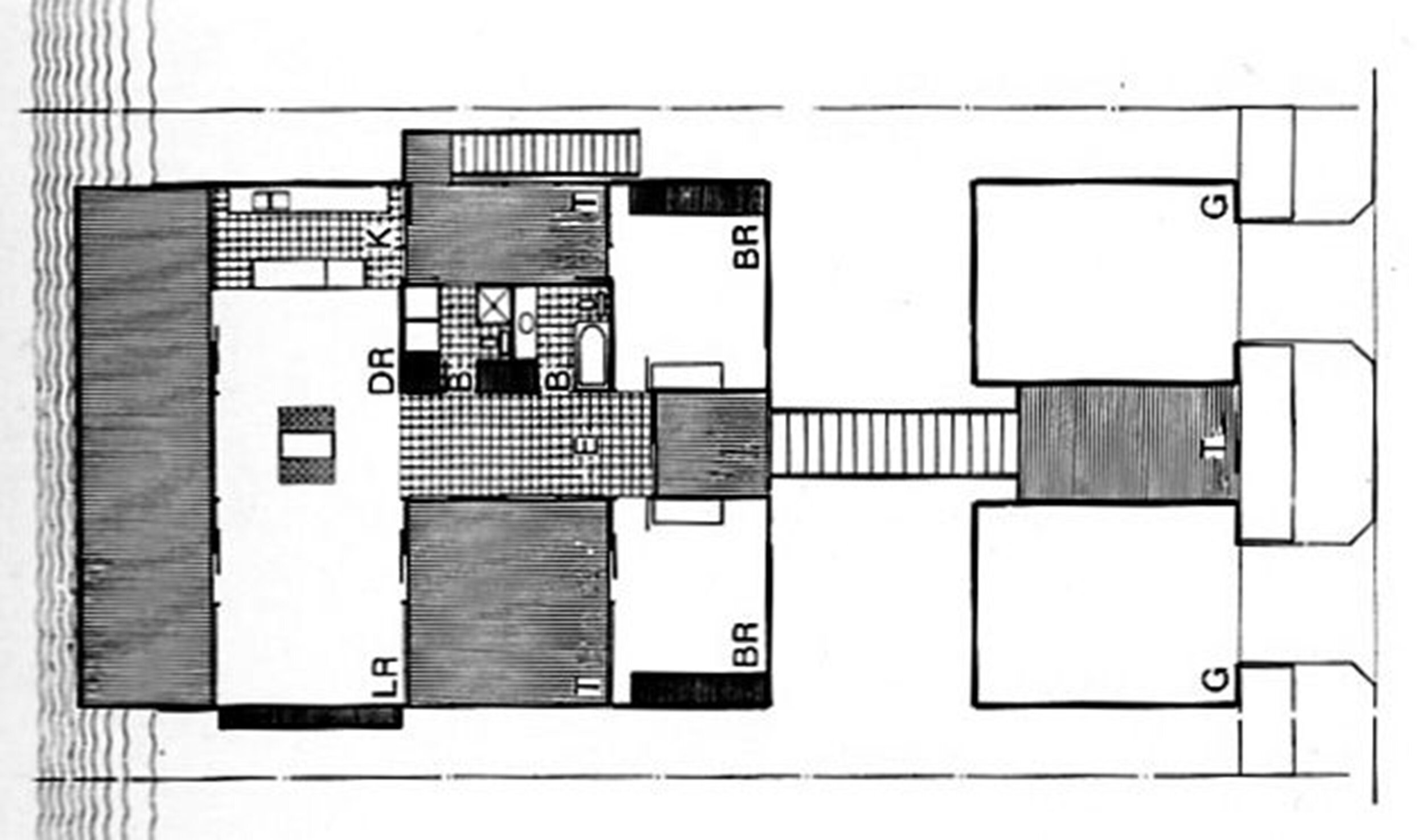

Hunt House Floor Plan, Craig Ellwood, Malibu, 1957

The Hunt House’s principal designer was Jerrold Lomax, who was an associate in the Ellwood office. The project is blank to the street: with two symmetrical muted garages and a central semi-opaque glass screen door greeting visitors with maximum privacy for the homeowner. Upon entering through this threshold the journey moves down towards the main pavilion via a stepped exterior terrace with peripheral views to the beach, building the anticipation for the upcoming views out over the Pacific Ocean. The house features a H-shaped plan to provide four distinct light filled areas and adjoining sheltered terraces. The interiors are rich with timber finishes and expansive glass walls, which are both effortlessly contained and breaking free of the box form. The project is able to cultivate the art of silence through the accumulation of refined details and modest design decisions to create a stark but mesmerisingly rich built form. This important project has been recently restored meticulously to the original state through the dutiful work of architects Barton Jahncke and Jim Tyler for the new owner and architect herself Diane Bald.

The rise of Ellwood’s career paralleled the founding of the Arts + Architecture magazine by John Entenza, a staunch modernist writer and campaigner. The early work of the émigrés architect Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler to Los Angeles, brought the International Style and pioneered the use of steel frame houses in the area. These innovative architects set the scene for the next wave of architects to adopt, refine and innovate the ideals of modernism as it evolved in the middle of the 20th century. It was John Entenza and his Arts + Architecture magazine that was a big motivator in taking residential modernism from the hearts of these early architects and placing it on the coffee tables and discussions of the broader public. Importantly it also prompted potential clients to become excited by the ideals of the modernist houses so glamorously portrayed in the publication.

Arts + Architecture, August 1957 Edition

The Art + Architecture magazine featured the growing modernist scene in Southern California and catapulted their images to the far reaches of the world – signalling to everyone that the nexus of functionalist architectural and casual living was being perfected in Southern California. It was the images of Craig Ellwood’s office that exemplified the attraction of Southern California and how the year round sunshine, palm trees and sex appeal highlighted the magic of truly unrestricted indoor/outdoor living. The man behind these photographs and a crucial member of the trio was the photographer Julius Shulman. His eye for capturing the spirit of these innovative projects was unparalleled. In combination with Entenza’s passion and Ellwood’s designs they portrayed an architectural nirvana to the world right at a point when the post-war housing boom was at its peak.

Case Study House #16, Craig Ellwood, Los Angeles, 1952-53

Arts + Architecture is most renowned for the Case Study Houses Program that it instigated. This entailed a series of houses prompted and promoted by the publication to typify, inspire and explain the evolving design ethos in Southern California at the time. This platform was utilised by many of the renowned architects of the era, who were able to both realise their evolving ideals and have them published far and wide. Ellwood’s office completed the Case Study House #16, #17 and #18 across a period during the mid 1950’s where his work were the only Case Study Houses completed and published from 1952 through to 1958, an era of tremendous prosperity for both mid-century modernism and the Arts + Architecture publication. These works were some of most elegant, refined and perfectly built outcomes ever featured in the magazine. The relationship between Entenza and Ellwood was extremely deep and aligned – their views of design and style were in harmony and together they were able to illuminate that living with good taste could be achieved on a budget. The dynamic trio of Entenza, Ellwood and Shulman crystallised the sublime within these small residential projects and projected it across the whole globe.

Case Study House #16, Craig Ellwood, Los Angeles, 1952-53

The evolution of the Craig Ellwood personal image went hand in hand with the rise of his offices projects. At the peak of his powers Ellwood was as well known for his animated lifestyle, as he was for his refined modernist dwellings. Ellwood surrounded himself with the picturesque dream of Hollywood: outdoor poolside living, beautiful people and fast cars. It was Ellwood who was leading the glamour stakes of the Southern Californian industry. He would be regularly seen dressed splendidly and either driving high-end European cars or strutting around his pet ocelot.

Ellwood was always an admirer of the work of Mies van der Rohe, whose rigid, functionalist machines epitomised the International Style. In the casual setting of Southern California Ellwood was able to first explore and then perfect adding informality to the Miesian box and in the process feminize the overall form. His work is often referred to as ‘Californian Mies’ and it was this irresistible combination of formality and lightness that is still mesmerising people to this day. In the outdoor focused setting of Southern California, Ellwood was one of the last people exploring the Miesian Box. He rejected the notions of plastic architecture and instead continued to perfect the structural purity in the box and how it can be utilised for the making of efficient spaces for living.

Rosen House, Craig Ellwood, Los Angeles, 1963

Ellwood was able to combine his skill for self-promotion with his genuinely innovative projects into a prolific rise by the end of the 1950’s. The climax of this came in 1963 with the Rosen House, lead in the Ellwood office by Jerrold Lomax. This project, like the many other Ellwood projects, did not require big budgets thanks to their efficient structural systems and refined detailing. The Rosen House is a white painted steel structure with expansive infill glass that exemplifies the goal that Ellwood was striving to achieve: a masculine functionalist form that is feminised to perfect the act of living and appreciation of indoor/outdoor living.

The Rosen House is a square plan punctured by a central courtyard that the interior spaces open onto. This courtyard allows the majority of the spaces to be naturally lit from numerous sides, creating a rich sense of transparency to the rigid steel structure. This openness is exaggerated by the elevated, wafer thin, white painted steel structure that disappears within the space, giving way to the views out to the landscape and through to other areas within the dwelling. The house is the realisation of all the refinements that Ellwood developed through the era of his Case Study Houses, which underpins the purity of Rosen House. The project refines everything to their primal function: the details are the design and the structure is the skin. With this project Ellwood was able to find clarity and demonstrate that the humanised engineered box in humble recognition of its natural surroundings can veer design discussions towards residential perfection.

Rosen House, Craig Ellwood, Los Angeles, 1963

During this peak period for the firm its size expanded substantially. The leading associates Jerrold Lomax, James Taylor, Ernie Jacks and others all played large and important parts in the projects. The office was very successful during this time, with around 100 buildings credited to the firm in total. The work largely focused on small-scale projects, with residential projects continuing to be the medium that allowed for Ellwood’s mantra to be best executed. One notable exception was The Art Center College of Design, Hillside Campus.

The Art Center College Hillside Campus designed by Ellwood’s office is a large bridge-like structure situated on an expansive site in the hills of Pasadena. The project has clear links to the strong functionalist projects of Mies van der Rohe, with the structural elements also becoming the key aesthetic and space defining aspect of the project. This gesture being the 192-foot spanning steel and glass bridge form that floats over a roadway below. The completed project houses the undergraduate programs, industrial design and film graduate programs, administrative and staff offices and two public galleries. The projects form may seem extravagant, however the design actually allowed for the most economical outcome to tackle the hilly site. The simple rectangular volume suspended on a steel super structure reduced the need for extensive grading and foundation work across the site.

The Art Center College, Hillside Campus, Craig Ellwood, 1976

The project is hailed as one of the Ellwood’s offices greatest achievements, being one of the few examples of his refined residential aesthetic transferring to the larger scale. It has been designated a local historic landmark by the City of Pasadena. The project was under construction from 1974 through to 1976 and was mainly lead by James Tyler as Ellwood neared retirement and became more removed from active projects. This project is one of the offices final commissions, with the firm officially closing just a year later in 1977.

The rise of modernism was fast and illuminating to an industry grappling with the expanding globalisation and the diverse ideas and construction techniques this created. Sadly as crisp and bright as this period of modernist architecture was across the middle portion of the 20th century it too began to receive pressure from evolving contrary design styles. The seemingly rigid and inflexible ideals of modernism were pushed aside in favour of the rising post-modernist trends of impromptu layering and historical appropriation.

Ellwood’s vision of structurally refined, occupant focused dwellings were striving for perfection, and at times came close to achieving it. His philosophy was eventually proven to be unsustainable without the ongoing impetus of the aligned factors that allowed for Ellwood’s residential projects to thrive in the post WWII setting of Southern California. This story is endemic of the broader modernist movement that pursued the desire to deliver good design to the masses. The promise of Ellwood’s was high, but it would eventually succumb to the mass production movement that was able to promote the uninspired and cheap outcomes of Levittown successfully to market. Ellwood’s refined simplicity, lost out to the homely instincts of façade deep nostalgia.

Craig Ellwood Portrait in front of his own painting

Ellwood was quick to acknowledge that his style of design was quickly becoming out of fashion and sought to distance himself from the industry with a shift to Italy. In this new setting, away from the bright lights of Los Angeles, Ellwood found a new home in the Tuscan hills where he started a new foray into constructivist paintings. With this transition and the closing of his Los Angeles office Ellwood’s architectural career came to a close.

Ellwood across the course of his influential career has able to explore with high levels of success the creation of refined, cost efficient dwellings utilising the industrial materials that evolved quickly following the Second World War. Whilst his personal life was complex, his architecture was quite the opposite. His architectural solutions were clear, legible solutions that brought a sense a calm to the often rigid, uninviting forms of modernism. Ellwood was able to utilise the rigour of perfecting details at all scales throughout a building to tame the usually inefficient American homebuilding industry and demonstrate the potential of well-designed, cost effective dwellings.

Steinman House, Craig Ellwood, Malibu, 1956

Typically the works of early architects Neutra and Schindler, or the later works of Eames and Koenig are referenced as defining the modernist architecture movement in Southern California. However, the work of Ellwood should be referenced as one of the richest peaks of the ideals of the era, in no small part thanks to the collaborations with Entenza and Shulman. Ellwood’s achievements were able to take residential design to its clearest and most efficient structural truth – something rarely achieved outside of his functionalist machines for living in Southern California during this period.

Interestingly Ellwood’s work is iconically of its time, but also still incredibly influential and resonate today. The ongoing popularity of his work demonstrates the success in his concepts and the longevity in their outcomes - especially when compared in stark contrast to the thin offerings of the Postmodernist movement. Ellwood’s work is still providing hope and inspiration to the architectural discourse of today thanks to the clarity and ease to which his buildings can be understood and studied. Undoubtedly his works are a snapshot of an era where numerous forces converged in Southern California to deliver some of the still most revered architectural outcomes.