November 2022

New National Gallery, Mies van der Rohe, Berlin c.1968

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is one of the most influential architects of the twentieth century. Across a sixty year career that spanned from Europe to North America, Mies developed innovative systems for the use of industrial techniques and materials with unparalleled clarity. His worked meticulously refined the burgeoning new era of steel, glass and open plan designs through a procession of canonical buildings that have inspired generations of architects since. His projects were not based on fashion or style, but rather sought to find the most rational outcomes within the framework of innovative construction techniques, ‘form-finding’ rather than ‘form inventing’.

Mies’s work developed an aesthetic that demonstrated the structural logic of the buildings with a firm understanding of the design lineage that had come before. His work continues to stand above his peers largely due to the rigour, poetry and artfulness embedded in the projects. He developed and perfected a series of building types that would become synonymous with the rise of modernity and the enduring character of contemporary skylines: the high-rise skeleton frame, the low rise repeated bay frame and the long span structures.

“From our position now, there’s no doubt to me that Mies was one of the great masters of the twentieth century, and all architects should kiss the feet of Mies van der Rohe because of his accomplishments and what we can learn from him.”

Potentially no other individual had a greater impact of the implementation of modernist design ideas across the US and internationally. This level of notoriety naturally led to a subsequent generation of architects who worked to define their careers in opposition to the legacy that Mies had created. The postmodernists that followed Mies attacked what they believed were ‘boring’ designs and rebutted the effectiveness of Mies’s spatial rationality as a redeeming quality worth proliferating. The undeniable clarity of Mies’s work rightfully with time has begun to once again be lauded by not only architectural purists, but the greater public for its enduring clarity.

Mies van der Rohe standing with model for S.R. Crown Hall

Mies was born in Aachen, Germany in 1886, originally as Maria Ludwig Michael Mies. He was the son of stonemason, but apart from a brief apprenticeship laying bricks, the development of his talents mainly lay in a generous education for someone from a family with relatively humble means. His father’s profession would have introduced Mies to materials and craft, a trait that we saw throughout his career in his predisposition for luxurious materials and precise workmanship. Mies was able to secure an apprenticeship with a local architect from 1901 to 1905. In this role he learnt about architectural practice and the importance of continual educational development, which eventually lead to his move to Berlin.

He made the move to Berlin in 1905 to maximise his evolving skillset. One of the first roles was with Bruno Paul, a talented Berlin designer, known for his work in decorative arts, furniture and interiors. After several years in this role Mies was recommended by his manager for a role with Peter Behrens in 1908. This was a pivotal move in his development as Behrens was a crucial modernist architects in Germany at the time. Behrens office became a concentration for aspiring young architects with not only Mies, but Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and several other important figures also working in the office around this time.

AEG Turbine Factory, Peter Behrens, Berlin c.1909

Behren’s work during this time focused on the concepts of simplified forms through a clear articulation of parts and exposed assembly techniques. The offices work in modular assemblies using cutting-edge materials such as glass and steel frames in pioneering manners. The AEG Turbine Factory by Behrens in 1909, which Mies worked on, celebrated the rise of industry, which would be a notion that became a guiding principle in Mies’s career.

Across work in several architectural firms in Berlin Mies’s expertise developed quickly and he began to also cultivate his own private work and soon developed a series of projects that would start his trajectory towards his eventual portfolio that would come to define the success of modernism itself. This path was quickly halted when in 1914 Europe imploded into war, initially Mies was able to continue his private practice work until 1915 when he was inducted into the army to serve across Germany and eventually in Romania. Following the war he recommenced his practice in Germany and developed several key concepts across this time. The first of these seminal projects was his glittering Glass Skyscraper, which was submitted for the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper competition 1921-22. This design was his first prominent post-war project and his initial chance to rationalise the changing global environment and start to theorise the potential paths forward for architecture.

Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper, Mies van der Rohe, Competition Entry c.1921

The gleaming skyscraper Mies proposed was the first theorised high-rise tower clad entirely in glass, an idea that harnessed the excitement of the post WWI rise of new materials. The project was initially overlooked, but with time has become heralded as the most innovative of the submissions, a glass crystal which contrasted dramatically from the historic city context. Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius had already begun to conceptualise the possibilities of modernism, and this was the first glimpse of Mies grappling with the concepts. Many now consider this to be Mies’s first project, as this was the moment his trajectory changed and began to unfold into the pioneering force of the profession.

Mies’s exploration of the flourishing ideas of modernism continued to grow over the next years. The next enduring project he developed was the Brick Country House of 1924. This project aggressively explored the evolving open plan theories becoming prominent, especially in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Brick Country House scheme eliminated the idea of rudimentary doors and windows, extending the interiors through to the garden spaces seamlessly. This level of spatial fluidity allowed for a series of interconnected spaces that reimagined the concept of the built form to support new ways for living.

Brick Country House, Mies van der Rohe, c.1924

Following stark economic times after WWI Germany began to find stability in 1924. The growing signs of prosperity led to proposals for a series of large municipal housing schemes being across Germany. To help facilitate the uptake of these public housing projects the demonstration project Weissenhofseidlung was launched to exhibit the opportunities of the new archetypes. Mies was appointed the artistic director, which thrust him into a position of leadership on the direction of modernism in Europe. The demonstration estate featured work from Peter Behrens, JJ Oud, Walter Gropius, Bruno Taut, Le Corbusier and many others. The work of this pioneering group hoped to transfer their promising work at smaller scales and spark energy in larger public housing where greater social good could be achieved. The schme is still widely lauded academically for both the built outcomes and the confluence of important young architects who demonstrated their views on the direction of modernism.

Weissenhofseidlung, Mies van der Rohe and many others, c.1924

During the late 1920’s Mies was cultivating his doctrine that modern architecture should extend beyond pure functionality to create a higher form of art. This was a mindset that he hoped could inspire the evolving industrialisation of the built form during the 20th century. The first built step in fulfilling these conceptual ideas took shape in 1929 when Mies realised one of the most recognisable projects of his career – the Barcelona Pavilion.

Originally known as the German Pavilion as part of the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, Mies designed a project that endeavoured to be a defining symbol for Germany following the recent dour economic times. The blurring between inside and out that Mies had been exploring in his earlier Country House projects found its clearest form in the Barcelona Pavilion. The project tested the enduring notions of space formation through a balanced set of tensions that prompted each visitor to acknowledge the ambiguities of the form – a trait that was so successful that future generations have come back to the project as a guiding light for the movement. This continual return eventually led to the once temporary pavilion being meticulously rebuilt in 1986 to give future generations the chance to visit the inspiring space in person.

The pavilion features a lush array of materials including travertine, onyx, green marble, plate glass, steel columns and pools of water. This project was one of the first times Mies used a modular grid to give the space a pragmatic layout and rationality that would evolve to be an enduring part of his later work in the US. The pavilions success lay in its ability to demonstrate that the evolving modernist movement can create forms that transcend the sum of their parts and begin to approach a form of poetics and art.

German Pavilion, Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona c.1929

While Mies was designing the Barcelona Pavilion during 1928, now fully entrenched in private practice, he was approached by the Tugendhat’s to design a home for them in Brno. The eventual project, the Tugendhat House, was completed in 1930 and was heralded for its demonstration of the potential of modern architecture. The house has a modest presence to the street, encompassing a single storey front form that extends horizontally and is constructed with a flat roof and austere façade of white stucco walls. The project innovatively used an industrial steel skeleton frame to achieve a dramatically flexible floor plan. This openness was best exhibited in the living space where a fully open space with floor-to-ceiling windows created an unparalleled connection with the exteriors for that time.

The Tugendhat House and Barcelona Pavilion both demonstrated to the public the ability of the somewhat monastic forms of modernism to hone the occupant’s senses and bring the spaces both inside and out into sharper relief. These ideas would continue to evolve all the way through to their fullest extents with the Farnsworth House and New National Gallery much later in his career.

Tugendhat House, Mies van der Rohe, Brno c.1929

The Bauhaus was a German art and design school that opened in 1919 and over its fourteen year duration helped to define a mindset of craft that would be a seminal piece of the evolving modernist movement. Originally founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar, the school has highly successful in nurturing students who would go on to achieve great feats internationally. Mies became the leader of the Bauhaus after first Gropius in 1928 and then Hannes Meyer in 1930 stepped down from the role. Mies was handpicked by Gropius to continue the school’s efforts, but eventually the ongoing scrutiny from the Nazi party prompted the school to close in 1933.

Around 1937 the opportunities for Mies and other modernist leaning architects in Germany began to disappear, as preferences shifted to architects more favoured by the Nazi regime. During this time of professional despair Mies received a letter from the Chicago School of Architecture at the Armour Institute of Technology, who would rebrand as the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in 1940. This letter would eventually lead to Mies travelling to the US in 1937 and ultimately accepting a role at IIT.

MoMA Catalogue, Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson c.1932

The work of Mies van der Rohe had already been exposed to US audiences through the 1932 MoMA exhibition in New York on International Modern Architecture. The Barcelona Pavilion, Lange House and Johnson Apartment were all featured in the exhibition and most notably the Tugendhat House was not only displayed, but also featured on the cover of the catalogue. This prominent position in the landmark exhibition propelled Mies into mainstream architectural consciousness across the US.

The underlying power of Mies’s work rested in that he did not oppose the history of the arts and felt that modernism should evolve from these inherent origins. This allowed for his work to have a unique mix of pragmatism and poetry. It was this niche that he felt could be best explored in America, a country he had long admired the technological ingenuity. Mies felt the US was lacking the underlying infusion of spirit and art in its built work and sought to provide a blueprint to do so across his time there.

“We know no forms, only building problems. Form is not the goal but rather the result of our work.”

When Mies first arrived in the US he quickly went about exploring and unlocking the architectural knowledge of the land. This first included securing an invitation to visit Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin East, a figure who since his Wasmuth publications of 1910-11 had a big influence on European modernism. Mies joined a previous Bauhaus graduate who had set up a New York office to work on some personal project opportunities. During this time talks with IIT progressed successfully and by the middle of 1938 he returned to Germany to settle his affairs and formally emigrate to Chicago.

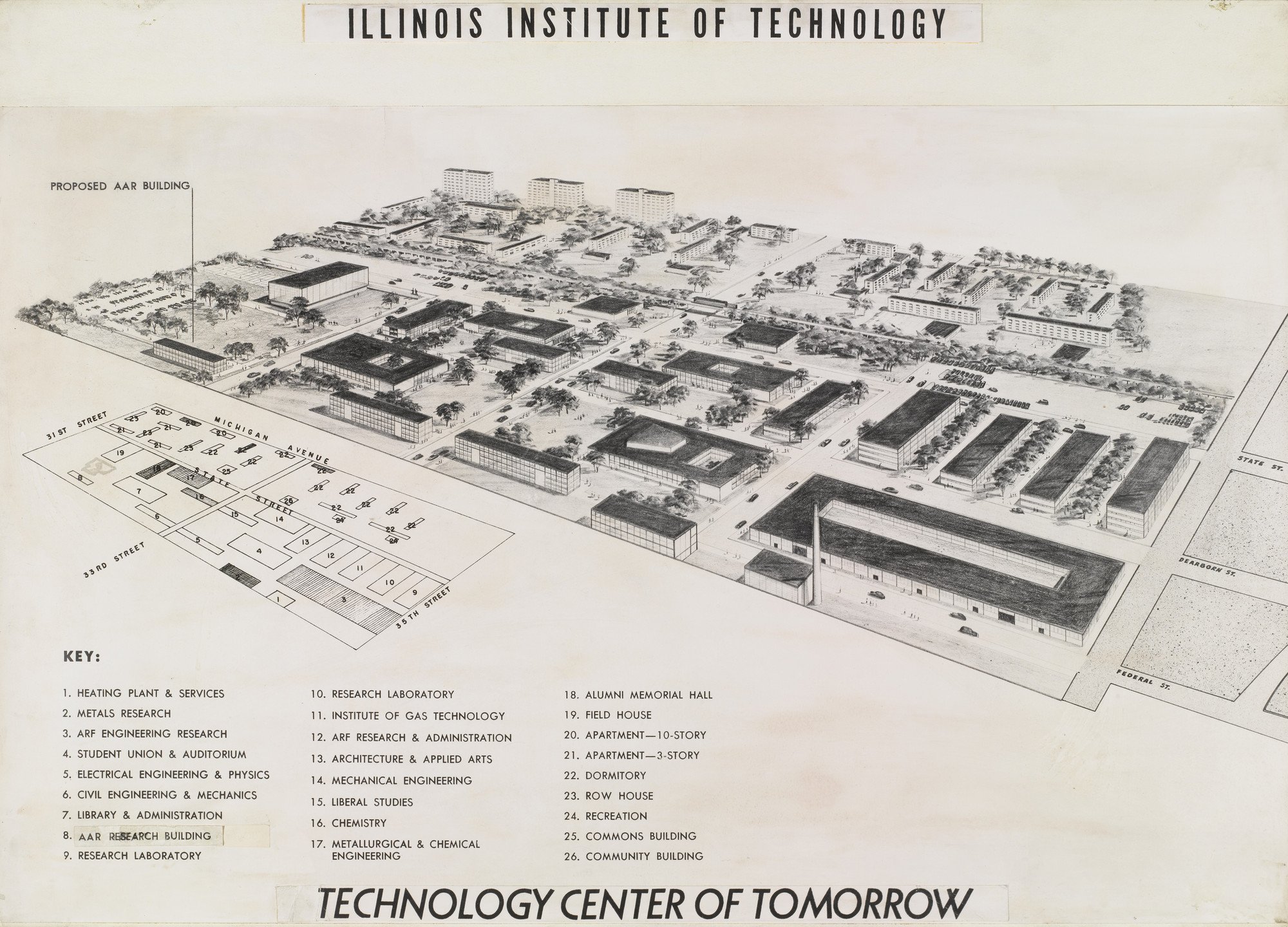

IIT Masterplan Concept, Mies van der Rohe, c.1942

Mies arrived back to Chicago at the end of 1938 to begin his new role at IIT. His first major task was leading the plans for the schools move from their existing location at the Art Institute of Chicago to a grand expansion at their main site in Chicago’s Near South Side. Mies defined the philosophy for IIT as: ‘The goal of an Architectural School is to train men who can create organic architecture’. The term organic had already become loosely defined by the landscape focused work of Frank Lloyd Wright, however as you see in the work of Mies his definition of organic had a much different focus. Mies instead envisaged organic design as the concepts of modernism reaching their fullest form through a synergy of technology, science and the arts - a built form shaped by the organic forces of the contemporary setting.

The initial masterplanning concepts for IIT began with overlaying a grid on the entire site to define building locations and connections. It was the first time Mies had used the grid as a layout system and eventually a 24-foot module was agreed upon as it was deemed to be the best fit for the room and building requirements. Interestingly the gridded system was a departure from the inside/outside ambiguity of his recent notable projects. Rather than being free-flowing spaces, the forms that were prompted by the grid at IIT were vertically extruded blocks of a much more industrial form lineage. The selection of this module was crucial to Mies and his design team as it allowed for a defining principal that could guide the continued evolution of the campus long after Mies’s tenure had ended.

Minerals and Metals Research Building, Mies van der Rohe, IIT Campus c.1943

The IIT masterplan was published in 1942 to critical acclaim as an innovative example of an extensive campus adopting modern design ideals within a landscaped urban setting. The design utilised an energetic layout of rectilinear one, two and three storey volumes that overlapped and slid past each other in an asymmetric manner to create a dynamic spatial campus experience. The modular nature of the forms allowed each building to be scaled to the needs of each department, whilst also maintaining a consistent campus logic. The advancements in structural systems that allowed these buildings to be realised were also confidently exposed, a trait he would continue throughout his career to define structures as a poetry of assembled parts. Mies stepped down as the director of the IIT School of Architecture and campus architect in 1958 not long after seeing the defining piece of the campus completed – the architecture building S.R. Crown Hall in 1956.

The one building in Mies’s scheme for IIT that departed from the rigorous module was S.R. Crown Hall, a dramatic building with timeless appeal. Crown Hall was his first realisation at an immense scale of an exoskeleton structure that enclosed a single universal space. Fundamentally Crown Hall is one vast room 120’ deep x 220’ wide x 18’ high. The space is dramatically spanned by four huge steel girders that are intentionally held in from the ends to enhance the impression that the glass box is being supported by the four towering pieces of steel. It is no accident that this iconic building was destined for the architecture building on campus, a rare opportunity for the students to experience first-hand the studies they are learning. The occupants of the building daily get to experience S.R. Crown Hall as an exemplar of modernism: a pure construction logic that refines the structural systems and space to their dramatically simplest form.

S.R. Crown Hall, Mies van der Rohe, IIT, Chicago c.1956

While working at IIT Mies’s own private practice in the US continued to develop his evolving concepts across numerous key projects. The first of these opportunities appeared at a dinner party in Chicago when Mies met Dr Edith Farnsworth and she described her desire for a second home in the countryside near Plano, west of Chicago. This house would eventually become the Farnsworth House, one of Mies’s most notable projects and helped inform large portions of what would eventually evolve into his later projects – most directly S.R. Crown Hall. Most of the early projects at IIT utilised large areas of brickwork, creating very dense and grounded projects. At the Farnsworth House Mies first theorised an expression of glass and steel to create a solitary enclosed space, a levitated form free from the heaviness of past designs. The steel columns were brought forward to allow the roof and floor structure to extend past the vertical elements and give the impression of the building floating in the landscape. This lightness was further accentuated by the white finish to the steel that creates a dramatic contrast with the surrounding nature.

Guests of the Farnsworth House arrive along the riverside path, observing the pavilion first at an angle. The building is raised 1.6m above the ground due to the rivers proneness to flooding – an issue that has only worsened with development upstream. After first sighting the project the entrance sequence takes visitors past the main form to the hovering lower steps that leads up to the main terrace and entry area. Once within this pristine white and glass pavilion the views out across the riverside site are framed to capture the ever changing seasons outside. Mies refined the Farnsworth House meticulously to achieve a volume with an extraordinary degree of openness that allowed for a near unparalleled appreciation of the surroundings from within its glass walls.

Farnsworth House, Mies van der Rohe, Plano c.1951

During the Farnsworth House design phase Mies crossed paths with Herbert Greenweld, a Chicago real estate developer who would provide Mies with his first opportunity to explore his concepts on high-rise projects. Mies and Greenweld shared the desire to develop a commercially viable example of tasteful modernism at larger scales to improve the living options for urban residents. Their initial collaboration led to the highly innovative 860-880 Lakeshore Drive project. This tower was an early exemplar of modernism’s potential and was a profound success, one that shaped the trajectory of not only Mies’s career, but the whole course of high-rise development.

The project at 860-880 Lake Shore Drive encompassed two residential towers. The site was located in a highly prominent spot for city bound commuters, drawing vast positive attention for the speed in which the innovative steel skeleton frame was erected. The towers were the realisation of the work started by the Chicago School of Architects who decades before developed the steel skeleton frame to support their high-rise projects. These early projects hid the steel behind a façade and it wasn’t until the advances many decades later in steel and glass construction that led to truest expression of the steel skeleton building. This honest expression at 860-880 Lake Shore Drive is seen most vividly from the lake where they rational tectonic form of the towers rise dramatically to symbolise the new age of buildings have arrived.

860-880 Lake Shore Drive were marketed as luxury apartments, but their underlying commercial success was their ability to be constructed extremely efficiently, at a cost often cheaper than Chicago Housing Authority developments. The towers prioritised the structural logic of the building above all else, with the steel grid of the façade becoming the enduring image of the towers. The success of this project would lead to several other projects between Mies and Greenwald and a whole generation of projects across the world who referenced Mies’s work.

860-880 Lake Shore Drive, Mies van der Rohe, Chicago c.1951 (900-910 Lake Shore Drive on the right c.1955)

Many perceive the pinnacle of Mies’s high-rise projects to be the Seagram Building in New York City, which opened in 1958. He was recommended for the project due to a liking for the tough character of his Lake Shore Drive towers. Mies sought to design a project that would break through the chaos of the New York streetscapes with a building that was starkly stripped bare as a beacon for progress and industry. The resulting project was Mies’s first commercial tower project and the new headquarters for Joseph E Seagram & Sons, located at the prominent 375 Park Avenue address.

The Seagram Building is an essay in opulent soberness. Mies went beyond the strictness of his earlier projects to add a layer of art and poetry to the project. Through the addition of lavish materials, dramatic proportions and advanced lighting systems the project became the most intense realisation of the modernist form. A key example is the steel I-beam extrusions are cast bronze, instead of typical steel profiles. The result is undoubtedly influenced by the projects collaborator Philip Johnson, who was a key contributor to the artistic exaggerations of technology that were innate in the Seagram Building. These flourishes often draw negative focus from design purists who feel the experience is deceiving, especially the surface mounted steel beams that Robert Venturi quoted Louis Kahn as saying that the building was “like a beautiful lady with hidden corsets”.

Seagram Building, Mies van der Rohe, New York City c.1958

The project is theatrically set back from Park Avenue creating a generous plaza in front of the thirty-nine-storey tower. This allows the full form to be viewed by foot traffic who are naturally drawn in by the public space provided. The form sits powerfully on the site, the density of the curtain wall grid anchors the project and creates a level of drama that was heralded when it opened in 1958. The buildings success defined a new type of grandeur for New York and brought great promotional success to the Seagram brand, both at day when the forecourt provides a natural meeting place or at night when the opulent lighting plan creates a modern spectacle to the famous skyline.

The final major project of Mies’s career would see him return to his home country to design the New National Gallery in Berlin, which opened in 1968. The project allowed Mies to realise the great form he had been seeking. A building that was able to truly harness the power of structural geometries of the time. The resulting form is both innovative and primitive, a highly engineered roof plane that hovers over a flexible universal space.

Mies had lived nearby the site of the new gallery many decades earlier, however the destruction of the area during WWII left it nearly unrecognisable. He returned to Berlin to accept the project and view the site in 1961, it was the first time he had returned to Germany since his emigration. The project site was sloped and lent itself to splitting the program into three parts. The first being an expansive lower podium to house the permanent collections, administration, loading and storage. The second was a grand upper terrace for all feature exhibitions and events that creates an unrestricted observation post, a tranquil opportunity to perch above the adjacent areas. The lower podium and main terrace literally lay the foundation for the third part, a gravity defying roof form that floats above the podium space. It is this roof form that the project is iconically known for, a huge web of steel perched effortlessly on eight steel columns set in from the corners. The new form does not look to recreate the past, but instead introduces a sublime moment to look out over the city that had seen so many recent terrors.

New National Gallery, Mies van der Rohe, Berlin c.1968

Mies was on-site when they lifted in a single day the fully assembled 1,200-ton roof as a single piece up on jacks at each column location. The eight columns that the roof eventually rested on where a cruciform shape that were refined rigorously to achieve the ideal aesthetic and structural relationship to the roof. Unlike at Crown Hall the ceiling was removed to allow the structural roof form to continue from inside to out. This allows the occupants to observe the immense weight of the roof and fully understand its monumentality. The rigour in which Mies perfected the form is best exemplified by the fact that the roof had a 5cm camber added to each corner to ensure the roof was perceived as being flat when viewed with visual distortion. Mies also extended these exhaustive refinements to the form and materiality of the building. Refining and eliminating element by element until the most primal form remained. It is under this roof plane, in the universal void that it creates, that Mies was finally able to realise what he felt was a modernist secular space.

The trip to Berlin to watch the construction progress of the roof installation would be Mies’s last trip to his home country. The combination of cancer and arthritis impeded his ability to attend the opening ceremony in 1968 and he passed away the following year. Near the end of his career Mies prioritised larger institutional projects that granted him the opportunity to continue exploring ideas around the pursuit of universal space. Given his physical constraints these projects, except for the Berlin gallery, were largely in North America in an attempt to not over extent himself.

Toronto Dominion Center, Mies van der Rohe, Toronto c.1969

The detractors of Mies’s work argue that his expansive portfolio of high-rise towers and clear-span pavilions are nominally identical and have led to a new paradigm of renditions that all look the same - creating a legacy of sterile urban monotony. Mies id often blamed for this traits of many post-war cities. Notwithstanding this negative doctrine around his concepts, the enduring influence of Mies’s work has had a level of impact on his peers and subsequent generations that few other architects have achieved. His work endeavoured to install a new mindset to rationalise the evolving construction technologies during the 20th century and provide a template that he hoped others would follow.

“We showed them what to do. What the hell went wrong?”

Mies’s work fundamentally did not succeed in the paradigm shift it had sought, although his work is still undoubtedly important in demonstrating an architecture that is able to embrace the dark and moody side of rationality to create outcomes that are both beautifully efficient and full of artful exceptions. His enduring legacy will be as a master of expressing structural systems poetically and how these advancements can improve the lives of their occupants.